BY Ashley Gauthier

For Sly Toussaint, spirituality comes in many forms. She is the founder and director of Centre Toussaint located on Fleury St. East in Montreal. With its Pan-African vision, the centre helps people melt into their culture through dance lessons, language courses, conferences, history classes and themed events.

“It’s around me. I work with many people who are involved in Vodou. I lived in Haiti for seven years, so I met plenty of people who practice Vodou,” she says.

Despite not being a vodouist—a Vodou practitioner—Toussaint has participated in Vodou alongside her family since her childhood. When she was younger and would get sick, her aunts would offer her special teas, oils, herbs and leaves as remedies, which are types of cures that are linked to Vodou.

A cabinet filled with oils, seeds and candles used in Vodou rituals from the Ofebalindjo Botanica Esoterique boutique located on Monselet St. in Montreal, Quebec. Photo by Ashley Gauthier.

In Montreal, Toussaint attended a ceremony that she describes as a regular celebration. Food is put out for guests and there is cake for dessert. Sticky rice, griot, chicken in sauce and other typical elements of Haitian cuisine are served.

“I think what characterizes it the most is the traditional clothing. Depending on the event, the colours will be different. There’s also always an offering table. Apart from that table and the way people are dressed, it’s really just traditional music playing the whole time, it’s really just like a normal party,” she says.

These ceremonies aren’t only for people to gather, listen to music and consume food. They also involve precise ritualistic practices such as presenting gifts to the lwas, or Vodou spirits in Haitian Creole.

Vodou practitioners can visit the Boutique De Variétés Botanica Flambeau to shop for the objects required in their rituals. One shelf is filled with candles of different shapes and colours. Owner Mirtha Germain picks up a red candle called balèn, the Haitian Creole word for whale. It’s handmade and carved from whale fat. Right next to it stands slim twisted candles made from beeswax.

“The black ones are to ask for justice,” she says. “With the white ones, you speak to the spirits. These ones are universal.”

Write your photo caption here. Photo by Ashley Gauthier.

Germain has been a manbo for the past 38 years, both in Canada and in Haiti. She defines Vodou as a spiritual connection to the ancestors and the lwas, and mentions that communicating with them is a two-way street.

“You have problems or you have a project, you ask your ancestors. You say, ‘Here, I have a project for 2025. Before the year is over, I want this, I want that.’ Then, you take a bath to remove all the bad energies,” she says. “After that, you take another bath to bring in all the good energies. Then, you make your promise to the ancestors.”

“Vodou is something sacred; you have to love people, help people, and share with others. That’s what Vodou is. It’s a lifestyle.” says Germain with a smile on her face.

Mirtha Germain proudly stands in her boutique located on Léger Blvd., in Montreal, Quebec. Photo by Ashley Gauthier.

Other practitioners focus on the connection between spiritual practice and mental health.

Kay Thellot is a certified manbo, an ethnotherapist and the founder of Prensip Minokan. That’s a foundation that focuses on an Afro-centered decolonial approach to navigate Black people’s obstacles in their mental health. She has regular therapy sessions in which she incorporates Vodou’s habits.

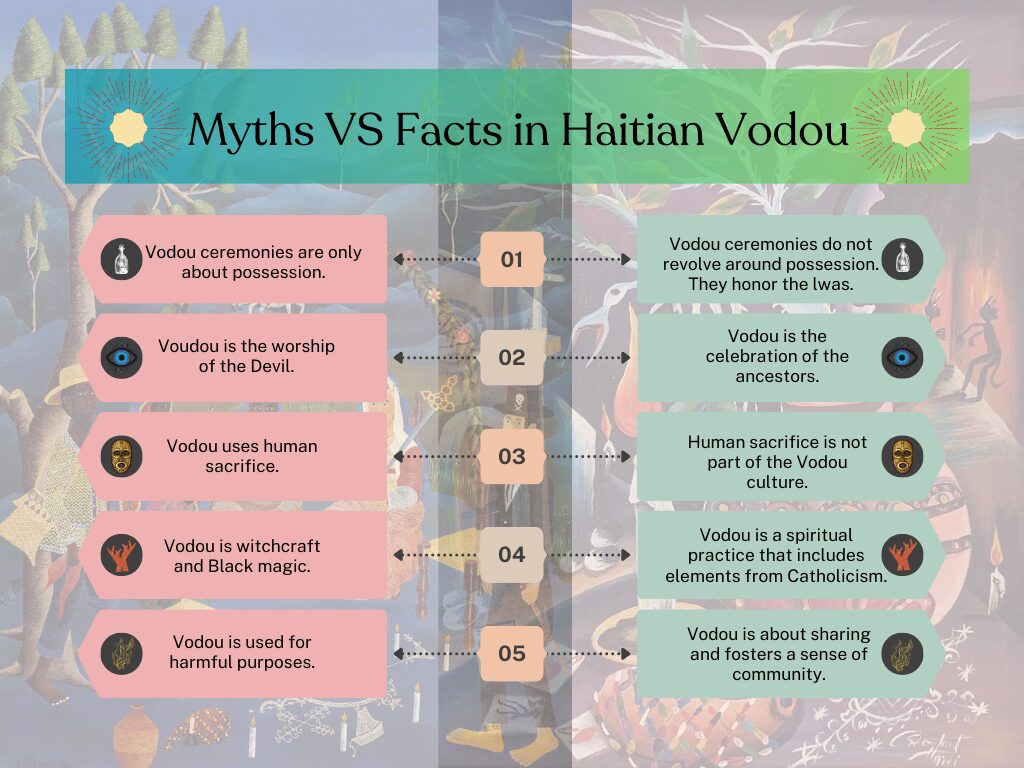

Thellot explains that to non-practitioners, the concept of Haitian Vodou can be thought of as something evil that is used to damage others. In reality, if someone does use the methods with harmful intentions, then it doesn’t classify as Vodou.

“There is definitely that idea of ethics and that it needs to serve the greater good. So when you’re bending nature outside of what it naturally does, there are severe repercussions. And so that’s witchcraft, not Vodou,” she says. “Vodou is like a baseball bat. I could use it to smash windows. I could use it to smash kneecaps, but I could also use it to have a beautiful baseball career. With the money I made, I could build schools and open services to help people, but it’s still just a bat of wood.”

A glimpse into Boutique de Varietes Botanica Flambeau showcasing an array of spiritual items. Photo by Ashley Gauthier.

Mylène Dorcé, Assistant Professor of Francophone African and Caribbean Studies at the University of Victoria, agrees with Thellot.

“Voodoo is still mistakenly associated with black magic, barbaric and diabolical practices, human sacrifice, or anything related to darkness and anything sinister,” she says.

One class she teaches is The Representations of Vodou in Popular Culture and Fiction, which looks at the wrong depictions of Vodou in Hollywood culture.

“My students always ask me why it’s so taboo and why we shouldn’t talk about this. I bring them back to the time of slavery,” says Dorcé. “During the day, slaves followed their masters and the colonizers. They went to Christian mass. During the night, they would get together and practice Vodou in secret.”

They had to be very cautious not to get caught as Vodou was frowned upon and would lead to severe consequences. This dual lifestyle is also the reason why many elements of Catholicism are present in the Vodou religion.

Let’s explore how enslaved Haitians blended Christianity with their traditional beliefs in order to protect their spirituality. Video by Ashley Gauthier.

Djab is a bokor who practices Vodou in a similar way that a manbo does, but works with more powerful entities. He prefers to use his mystical name to protect his identity because he’s concerned that people who are not familiar with his title might think he is evil.

Djab says misconceptions about Vodou being linked to Devil worship are rooted in fear since the spiritual practice is underground.

“Just because Vodou is something a bit unknown, but it’s also powerful,” he says. “In relation to what we went through with slavery, Vodou was demonized to say it is something bad, it’s something evil. But yet, we were beaten, we were killed and we were raped in the name of Jesus Christ.”

Toussaint believes that Montreal’s level of acceptance towards Vodou is growing.

“There is more demystification happening. More people are educating themselves, more people are understanding, and more people are becoming curious. I think that there is a better understanding of what Vodou really is.”

Look at the truths and the lies within Haitian Vodou. Photo by Ashley Gauthier.

While Vodou is an underground religion in Montreal, practitioners are free to organize public events, such as the International Festival of Vodoun Culture. These types of social gatherings have a direct impact on acceptance and awareness.

“Vodou is something that’s expanding a lot. It’s really something that’s more democratized than we might think,” says Toussaint.