Aaron Bauman & Jiawei Hong

Sifting through months of collected waste, Florence Tremblay collects materials for her next sculpture. Plastic pull-tabs, bread clips, cardboard boxes and plastic bags, all pieces to the puzzle. To some, everyday waste dies when it goes in the bin, but Tremblay finds art.

“It’s mainly made with metal mesh and repurposed materials like cardboard pulp,” she explains, describing her most recent featured artwork “Maudit Colon”, a 195 cm structure in cardboard-mâché, with inserts of molded elements and fragments of waste.

Maudit colon (Damned Columnizer), 2025 Repurposed cardboard pulp, metal mesh, packaging remnants, shipping boxes. 15” x 15” x 89”. Photo and work by Florence Tremblay.

“The cardboard pulp is from cereal boxes and packaging, I just go for the bins,” Tremblay says. Plastic, often vilified, finds a new life in her hands.

Tremblay’s work is not just about aesthetics; it’s about ethics. She considers the entire lifecycle of her creations, from sourcing to disposal.

“I’m trying to think about the afterlife of my work…. How easily can I recycle them?” she says.

However, working with repurposed materials presents unique challenges. Tremblay finds that it requires patience, resourcefulness, and a willingness to adapt, but it also fosters a deeper connection with the materials themselves.

“You get closer to them, it’s a very intimate relationship, more intentional.”

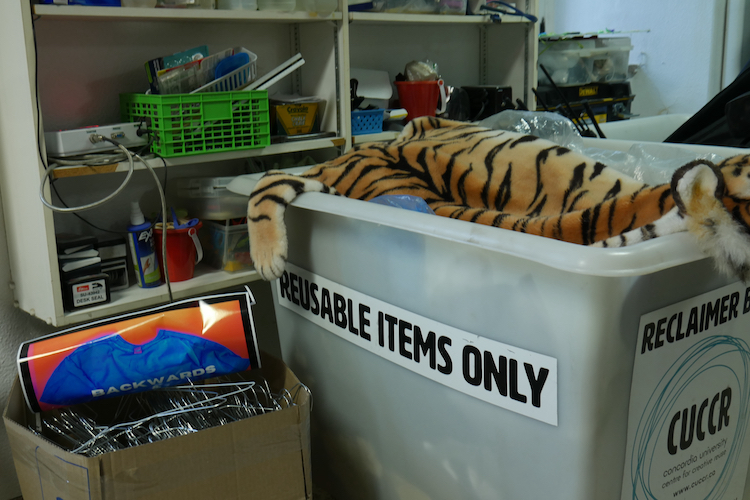

Bins and storage containers of the CUCCR filled with recycled objects waiting to be sorted and given new life. Photo by Aaron Bauman.

Montreal is celebrated for its vibrant and diverse arts scene. A city mandate requires new buildings to put between 0.5 per cent and 1.5 per cent of any construction budget into art.

But where the city is spending millions, a quiet few are scavenging through waste. Unlike the typical imagined artist sourcing their materials from art supply stores these clever few are discovering them in the waste produced from everyday life.

Students checking out at the CUCCR with recycled materials they will be using for a class project on alternative technology. Photo by Aaron Bauman.

A hub for this kind of creative transformation is the Concordia University Centre for Creative Reuse (CUCCR). Far more than the regular high tech and highly funded recycling centres, CUCCR functions as a resource for anyone seeking inspiration and raw materials for their projects. This is where one person’s trash becomes another’s treasure.

Since September 2024, the CUCCR has seen 2,443 checkouts estimated to have saved visitors $90,000 on supplies, preventing almost 10 tonnes of waste from reaching landfills.

The CUCCR’s impact does not stand tall compared to the mountain of waste produced by Montrealers which amounted to 923,752 tonnes in 2023 (or 430 kg per person). Anna Timm-Bottos, the CUCCR’s founder and manager, knows this.

“It’s been really amazing to see how every little bit that people take away, to give new life, to recycle in a like new way,” she says. “Even though it’s not a lot, it all adds up.”

The city itself is working towards ambitious targets outlined in its 2020-2025 Waste Management Master Plan, with a goal to reduce waste generation to 399 kg per person and achieving a 70 per cent diversion rate (recovering materials away from landfills) by 2025, with a current recovery rate of 50 per cent in 2023. These steps are part of a larger, long-term vision aiming for zero waste by 2030.

“I look around and I see delayed garbage. This is not gonna stay out of the landfill forever. You know, it will unfortunately probably end there,” says Timm-Bottos. “But instead of it being just single use, we give it a little bit more time to live and hopefully prevent new purchases for a little bit longer. And that is the best we can do in this current context.”

Smaller recycling centers like that of the CUCCR are needed in the city’s plan for a green revolution. Karel Ménard, director of the Quebec Coalition for Ecological Waste Management believes that most residents don’t give their garbage a second thought. Proposing that if we were to dump the waste somewhere on-island or close by, people would become more aware of the impacts of their waste and work harder to limit them.

According to Ménard, if Montreal is to make a shift in its habits, visuals are everything. This is where the CUCCR’s small ripples can make a real splash.

Anna Timm-Bottos, the CUCCR’s founder and manager working on a collage of recycled art. Photo by Aaron Bauman.

In her eight years operating the CUCCR, Timm-Bottos has learned to see the inherent potential in what others have carelessly thrown away.

“I look around and I see delayed garbage. This is not gonna stay out of the landfill forever.”

Knowing that her work is only delaying the inevitable, Timm-Bottos has learned that sometimes materials just have to wait for the right person to come along and breathe new life into it.

“We give materials a little bit more time to live and hopefully prevent new purchases, it’s the best we can do,” she says.

For many, the thought of recycling is not a thought at all, in fact, nearly half of Montrealers do not use their composting bins despite a recent push to provide residents with their own brown bins. This, according to researcher Annabel Durr, is a problem of accessible education.

Durr actively engages the community by explaining sustainable art practices through free hands-on workshops. She believes that art is one way to promote a more sustainable Montreal.

“It’s really a lot more accessible to a wide range of people, especially those who might not be formally educated about what sustainability means,” she says. “It’s an action you can take that can help make you feel like you’re contributing toward environmental change and sustainability.”

A cyanotype print made by Annabel Durr for one of her workshops. Photo by Annabel Durr.

Durr believes art can create a ripple effect of environmental awareness.

“It is a great way to be able to show it to other people and then have other people be interested and engaged as well,” she says.

Beyond just individual actions, community building is central to Durr’s educational mission.

“I think that is a big fundamental part to changing these bigger issues, [by] building a community that is trying to do these things, constantly experimenting with ways to tackle the environment or change the system that way,” she says.

Durr has witnessed firsthand the connections forged through her workshops.

“Once you build these connections in a community that is trying to go in a way of sustainability, you open yourself up to all of this knowledge and other ways of also having fun being sustainable,” she says.

As electronic waste increases in Canada, experts and entrepreneurs are working to extend the life of our devices through repair and reuse before recycling. Video by Jiawei Hong.