BY Rania Salah

In June of 2015, the Canadian government vowed to follow through on 94 Calls to Action regarding aboriginal communities. They came after years of hearings by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

A decade later, very few of those calls have been followed up.

“The government is a large entity. The individuals are sincere, but collectively have they made it a priority like they said they would? No,” says Jessica Vandenberghe, assistant dean at the University of Victoria and member of the Dene Thá First Nation.

One change that has been made is the inclusion of Indigenous history in primary and secondary curricula.

“Going from essentially learning very little to how much they are learning now is significant. It captured the lived experience of people who went through something awful. What they stated happened couldn’t be denied,” said Vandenberghe.

The 2008 mandate for mandatory education about Canada’s abusive history of forcing aboriginal children into residential schools applies to more than just schools. Mandate 67 also requires Canadian museums to visibly depict Indigenous histories and culture.

Taken at the McCord Stewart Museum’s “Indigenous Voices Today” exhibiton. Photo by Rania Salah.

Steve Bonspiel, editor of the Kahnawá:ke-based newspaper The Eastern Door, says education has changed Indigenous communities as well.

“People didn’t even really know about Residential Schools: including people in our own community,” he says. “That’s the way they were set up: to be silenced. Silent things that happened stayed in our past. Some people are only discovering now that their grandparents or parents went to Residential Schools, because they were so ashamed.”

The increase in awareness of Canada’s unfiltered history does not come easily.

“It challenged everybody to do something: from churches, to government, healthcare, enforcement,” says Vandenberge. She suggests the next step should be mandatory awareness training for all government employees.

Primary school on a field trip to the McCord Stewart Museum’s “Indigenous Voices Today” exhibition. Photo by Rania Salah.

Bonspiel explains that there was a lot of hope at the beginning of the Truth and Reconciliation’s project but it quickly disappeared.

“There was a lot of hope that things would be different. Unfortunately, as governments do, they failed. They didn’t live up to a lot of them.” said Steve Bonspiel.

He believes the next priority should be land claims.

“Realistically, in order to properly implement the 94 recommendations, the underlying and overarching theme is land,” he says. “We’re on small reserves for a growing population, faster than the mainstream rate, and we need land. We need places to practice our traditional pursuits.”

Indigenous communities now only make up an approximate 5 per cent of Canadian territory.

“Even the land that’s being used now, it was never given up or purchased: most of it was just taken. We don’t get a dollar,” Bonspiel continues. “You can’t move forward as communities and as people unless land claims are seriously discussed, and not trying to short change us.”

Viewer reads on the glamorization of Canadian history. Photo by Rania Salah.

Bonspiel is not alone in this sentiment. Tommy Deer, cultural and historical liaison at the Kanien’kehá:ka Onkwawén:na Raotitióhkwa Language and Cultural Center, reiterates the importance of land.

“Without respect for treaty obligations that establish our foundational relationship based on coexistence, non-interference, and mutual respect for each other’s independence – any attempt at reconciliation is empty and meaningless,” Deer says.

More than just the land itself, he outlines the importance of treaties and past promises that were made with colonizers.

“When the Dutch first came into our territory in the early 17th century, they were motivated by establishing a trade network with our people. Our ancestors felt that in order to have an economic relationship, there needed to be a foundational relationship first. We offered them the Two Row Wampum relationship,” Deer says. “This symbolism is reflective of the desired relationship between the Rotinonhsón:ni Confederacy and the Dutch, based upon coexistence, non-interference, and a mutual respect for each other’s independence.”

Taken at the Mccord Stewart Museum. Photo by Rania Salah.

But Deer also believes that no matter how many calls to action are fulfilled, true reconciliation doesn’t exist..

“Canada has historically refused to accept that it has inherited the relationship established with its British predecessors, so that means there has never been a time that Canada has had a state of peaceful relations with the Rotinonhsón:ni Confederacy and therefore the term reconciliation is a misnomer,” he says.

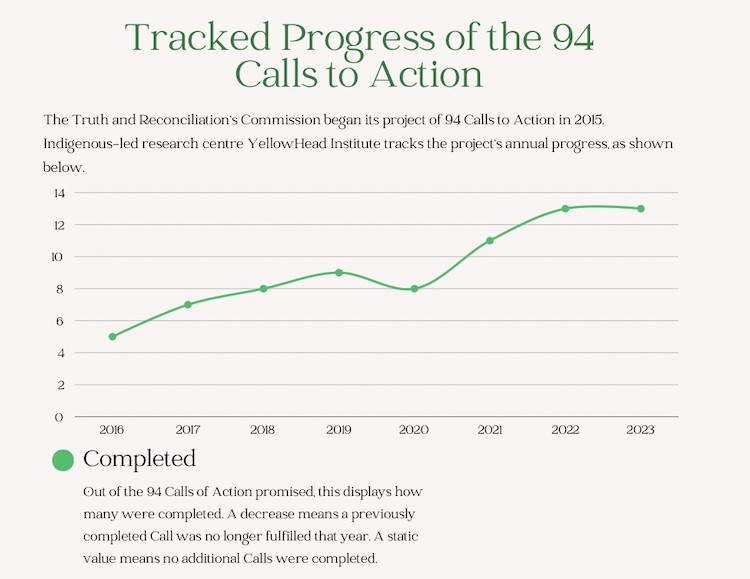

As of 2023, only 13 of the 94 Calls to Action had been successfully completed.

According to YellowHead Institute, an Indigenous based research centre, “if Canada continues at this pace, it will take another 58 years until the Calls to Action are completed, meaning that Indigenous peoples will have to wait until 2081 for reconciliation.”

A visual depiction of the 94 Calls to Action’s progress status. Graph by Rania Salah.

Although the Truth and Reconciliation’s Committee’s progress has been slow, it doesn’t mean that progress can’t be made through other means.

“There’s been many movements over the last century, and I know this won’t be the last movement,” says Vandenberghe. “We will not give up. There will be more.”