BY Matthew Daldalian & Adamante Balin

In a small apartment near Sherbrooke metro, wine enthusiast Ilesh Thomas reminisces about his childhood near Ontario’s Niagara region. In his hand rests a glass of ice wine—the kind he’s taken a liking to only recently, after stumbling upon a forgotten bottle from his last visit home.

“I’m from Ontario. I’ve very much heard of ice wine before,” Thomas said, a smile creeping across his face as he recalled his earliest sips back in his teenage years. “When I was growing up, my parents would frequently pair it with desserts because it’s very sweet […] You would just have it with a less sweet dessert.”

He still remembers the narrow crystal glasses set on the dining table, shimmering under holiday lights, each sip leaving a honeyed imprint on his tongue.

Ilesh Thomas sips on chilled ice wine in the evening hours. Photo by Matthew Daldalian.

These warm memories form a stark contrast to a reality in which many Canadians are discussing less — or even drinking less — the beverage known as ice wine.

It comes as Canada’s overall wine exports are booming. According to a report from Statista, the volume of wines exported from Canada increased by eight per cent in 2023, or over 16,000 kilolitres. That continues a trend of more than a decade.

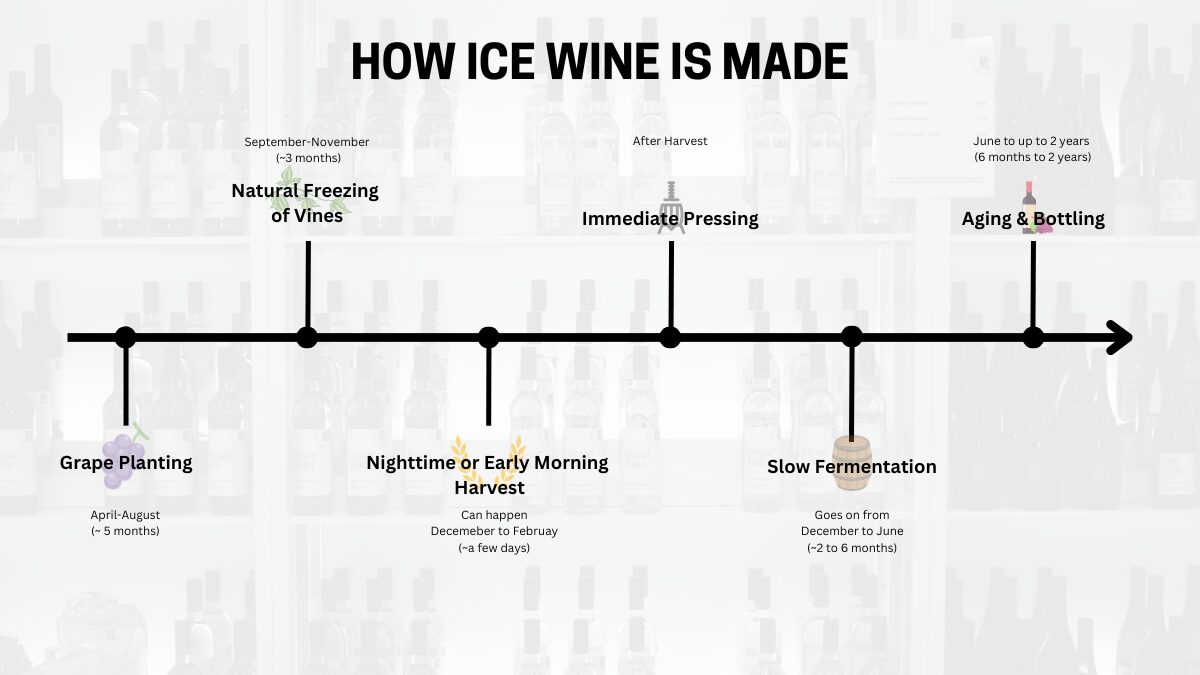

Ice wine—created by pressing grapes still frozen on the vine—has become a hallmark of Canadian beverages, largely due to reliably cold winters. For Quebec’s producers, though, standing out against international heavyweights like Germany or even Ontario’s Niagara proves to be a tall order.

The process of making ice wine, as described by Benoît Giroussens. Timeline by Matthew Daldalian.

“It’s a popular product—but for tourists,” says Sébastien Léonard, a director at Société des alcools du Québec (SAQ). “We don’t sell that much to people that live here, but we sell a lot to tourists. […] For ice wine, if you read any magazine in Japan, they will say it is the best ice wine on earth in Canada.”

Léonard believes the story does not end at tourism alone; local tastes also play a defining role. “Two reasons I think so is that right now in Quebec, sweet products are not really popular,” he explained. In his view, wines like port, sauternes, and ice wines have all been overshadowed by Quebec’s shift away from high-sugar drinks.

“For people here, we don’t really check what is popular anywhere,” Léonard adds, suggesting there is minimal local promotion or education around ice wine.

Sommelier and wine critic Jessica Harnois argues that Quebec ice wine is more than just an afterthought.

“Quebec ice wine has evolved from being a niche regional product to gaining greater recognition internationally, though it still has some catching up to do compared to Canadian heavyweights like Ontario’s Niagara region,” she says.

While such products have won accolades at wine festivals, Harnois sees rising concerns with consumer behavior.

SAQ’s selection of ice wine products on Ste Catherine St. Ouest. Photo by Matthew Daldalian.

“Festivals and international wine competitions have played a significant role in enhancing visibility but people eat and drink less ‘sugar’ these days,” she says.

Nevertheless, Harnois is optimistic about the future of ice wine.

“Younger wine drinkers, in particular, are more curious about the backstory of a product, how it’s made and its environmental impact,” Harnois says. Additionally, “pairing ice wine with savory dishes or cocktails is a growing trend, helping shift its image from being exclusively a dessert wine.”

Beyond economic viability, some see ice wine as reflective of Quebec’s artisanal spirit. Dr. Jordan LeBel, a marketing professor at Concordia University, underscores ice wine’s place in Quebec’s broader gastronomic identity.

“If we think of the products that we associate with Quebec, you’ll have poutine […] and at some point, if you just ask anyone in the street, I think ice [cider or wine] is going to come up in the nomenclature of food products that we associate with our identity that we care about,” he says.

However, LeBel is straightforward about ice wine’s niche status.

“Because if you’re just gonna buy a bottle and you’re gonna have it with a piece of dessert or a piece of cheese, which is sort of the standard thing, well, there’s just so much you’re going to use,” he says.

In other words, ice wine is rarely part of anyone’s regular shopping list; most ice cider or wine producers are artisanal shops, and producers often do not see a great return on investment.

Benoît Giroussens, the technical director for vineyard Coteau Rougemont, believes changing weather patterns could help local wine production in the long run.

Coteau Rougemont’s selection of ice wine products. Photo by Matthew Daldalian. Photo by Name.

“Over the years with climate change, we have more degrees, so we have a maturity that is better for the grapes,” he says.

Giroussens explains that winter extremes can kill vines that thrive in Europe, but Quebec’s warming temperatures may expand the range of viable varieties. For producers of sweet wines, a longer growing season could yield grapes with a higher concentration of flavors—a key element for richly balanced ice wine.

This video examines climate change and its effects on wine production and its potential effects on the production of ice wine. Video by Adamante Balin.

However Giroussens is realistic about how far this advantage might go in elevating Quebec to a world-renowned region. When asked if Quebec could become a major wine leader, he is unequivocal: “No, absolutely not.”

LeBel laments that many producers of ice cider or ice wine in Quebec have drifted into a difficult position. “If you’re just gonna buy a bottle […] once in a while to give as a gift […] you’re not getting a high frequency,” he says. “So the product has ended up in what I would call a, from a marketing perspective, dead end cul-de-sac.”

According to LeBel, artisanal shops often resist partnering with large corporations capable of boosting distribution and brand recognition.

Coteau Rougemont standing in front of a dead vineyard. Photo by Matthew Daldalian.

A handful of producers have begun experimenting with varied packaging, such as smaller bottles aimed at younger or more casual buyers. Others are considering sparkling versions of ice wine or cocktails mixing ice wine with spirits. Yet, according to LeBel, the broader beverage industry has leapt ahead in experimentation. Ice wine makers have largely missed this surge.

For Thomas, ice wine remains a cherished taste from his past, something he could imagine sharing on special occasions.

“I think it would have to be very intentionally brought in […] probably the most realistic incidents would be if I throw a dinner party or something like that and add it as part of the dessert course,” he says, before laughing at the idea, conceding that most of his friends in Montreal barely know about ice wine.