BY Jeremy Cox & Ana Acosta

Leonidas Mihalochristas runs his own private coaching business at MyGoal Hockey in Dollard-des-Ormeaux. He is aware of the changes the hockey world has been through.

“I think growing up we didn’t have all this stuff that wasn’t around,” he says. “So that’s why I think the game’s a little bit faster and better and we see kids starting hockey younger and younger. Now if you’re not doing private training, you’re going to fall behind because everybody’s doing it.”

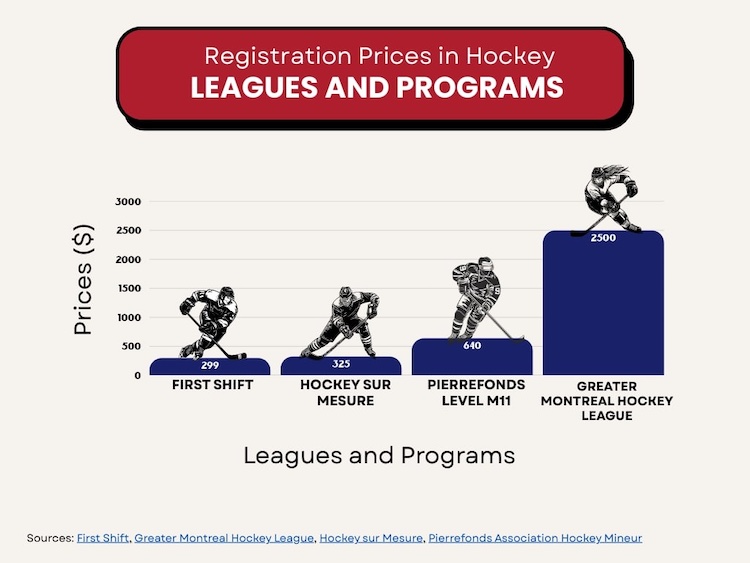

Mihalochristas also coaches for the Young Kings minor league team in the Greater Montreal Hockey League, which is privately run. Registration for the season costs $2,500 per child. The way he sees it, parents want to spend more on professional coaches rather than parents who volunteer, and for their children to play with more official rules in order to have more exposure and experience at an earlier age.

Small hockey leagues are essential in Montreal to shape young players and build stronger communities. Here, we look at local teams like Hockey HRS that are making hockey accessible for all kids.

In contrast, the registration cost for a Pierrefonds Atom level team, a public inter-city team for players under 11 years old, costs $640.

“Now you’re seeing numbers go down because less kids are signing up to city hockey, which I’m gonna guess how Canada goes off city hockey,” he says. “And more kids are signing up to private hockey.”

There are other ways to play hockey for people who can only play on a budget.

Hockey Canada provides services to help children get onto the ice. That includes the Hockey Canada Assist Fund, which gives $500 to low income families. It helps up to 2,000 kids a year.

Hockey Canada also provides the First Shift program for families who are new to the sport. The program includes head-to-toe equipment, equipment demonstrations and six weeks of safe-to-play on-ice experience.

According to Hockey Lac-St.-Louis general manager Raymi Gélieau, the cost of equipment is not the most limiting factor to get children to play the game.

“The biggest impact is the cost of ice. There’s ways of getting equipment from Sun Youth and stuff like that, they do equipment drives” says Gélineau. “So to get equipment at a lower cost is sometimes a possibility.”

He says that although public rinks that are entirely owned by the city will be less costly for associations to rent, but some public rinks aren’t particularly well maintained. The Macdonald arena in Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue and the Beaconsfield Arena were closed for the 2024-25 season, while the Martin Lapointe Arena in Lachine has been closed since 2021.

Gélineau was able to implement the Hockey-Sur-Mesure program to allow access to lower-income families. The program is less expensive for players, and the league is run on a lower budget. There’s no money spent for team transportation, just local gameplay. Only two associations started to run the program in its first two years of operation. Gélineau hopes that more associations will follow suit in the future.

“They have to want to do it. But now people are starting to realize this is a need from their communities and they want to go toward that,” he says.

Registration Prices in Hockey. Bar graph by Jeremy Cox.

Hockey Canada reported just under 450,000 players younger than 18 years old having registered for the 2023-2024 season. And although sign-ups have exceeded their pre-pandemic totals, they aren’t what they were in 2010.

The domain of hockey equipment and retail is becoming more costly. Today, prices for new hockey skates are reaching four figures, like the Bauer Supreme Shadow skates which are pricetagged at over $1,300. The usual price for a high-quality senior composite hockey stick can reach $450, such as CCM’s Vizion.

Jesse Shea-Cowper, owner of hockey equipment shop Sport-Au-Gus, has felt the increase in costs.

Jesse Shea-Cowper working at the Sport-Au-Gus cash register. Photo by Jeremy Cox.

“Do I think that $400 for what they’re doing for the stick is a lot? One hundred per cent,” he says. “[Large brands] sink millions and millions of dollars in the branding and that’s what happens at that level.”

Those brands set a price for equipment, which distributors such as Sport-Au-Gus must respect. With the rising cost of manufacturing, the price will follow suit.

According to Shea-Cowper, there will always be a demand for the highest quality equipment, regardless of the prices.

“You’re also getting tons of branding thrown in your face, right? It’s 15, 20 seconds of a Tik Tok, of an Instagram shot of the ice, snapping around with the influencers, with a $400 Twitch stick,” he says.

Shea-Cowper knows that running a small business gives him a chance to give back to the community. He believes he can provide a safety net for those in need by providing discounts.

Jesse Shea-Cowper sharpening a pair of skates. Photo by Jeremy Cox.

“You know, this perception of the barrier to entry because of the high level of equipment kind of gets put on the back burner,” he says. “And really people understand the true passion that goes in the game and I want people to just love the game.”

Yves Mouchaka, manager of second hand sports equipment store Play It Again Sports, says that constantly changing products have meant fewer people looking to buy used equipment.

Equipment on display at Play It Again Sports. Photo by Jeremy Cox.

Twenty years ago, Mouchaka was able to resell used equipment for around 50 per cent of its original price. Today, a skate could resell for less than one third, as equipment updates happen about every 18 months, rather than every four years.

“Athletes read up on what’s coming up, what’s new, and they all want to test it, try it out, unlike my generation, which is the 70s and 80s. We like to hold on to our gear,” says the manager. “I would say the generation of the 2000s are clientele which really want to see what’s new. ‘Let me give it a shot and invest.’”

It is possible to say that certain investments can provide gateways to better resources. Although, that doesn’t come without persistence first.

Marc-Alan Araujo is 17 years old. Since the very first day he stepped onto the ice at eight years old, he knew he wanted to be a hockey player. He played for the Lac St-Louis Arsenal AAA team, the highest level of minor league hockey, before being admitted to Shattuck-St. Mary’s boarding school in Minnesota, which hockey legends such as Sidney Crosby, Nathan MacKinnon, Amanda Kessel and Jonathan Toews have attended.

Marc-Alan Araujo. Photo by The Hockey USA National Championships.

To achieve his goal, Araujo dedicates countless hours on the ice in order to improve his game. His father, Marc, was present with him for every step of the way. That includes driving his son for weekend trips to tournaments around Canada.

“You don’t want to say no because at the end of the day, your kid needs this,” Marc Araujo says. “So for the poor kid who can’t pay it, definitely it’s a loss for him because this is where exposure happens.”

The admission for tournaments hover around the $600 to $700 price range. If Araujo is spending on hotels, gas, and food, a weekend could easily cost him $3,000.

“You know what the truth is, is that as a father? It was great for me,” he admits. “Because it was time I was spending with him, so I had a point. I sold my companies, you know, just to spend that time with him.”

At Shattuck-St. Mary’s, Marc-Alan Araujo has exposure to top-of-the-line resources. He has access to ice treadmills and virtual reality headsets, which simulate in-game NHL experiences.

All that dedication has paid off. Araujo was able to dominate in the USA High-School Nationals, and scored the winning goal in the finals, getting his school the championship.