BY Evan Lindsay & Chantal Schromeda

Tabena is a parent of two who recently became a member at The Depot Community Food Center in NDG. Tabena asked us not to use her full name because her friends do not know she’s using a foodbank. Before the pandemic, Tabena worked in factories and as a housekeeper. But when those jobs started to disappear she struggled to buy healthy food for herself and her kids.

“Before, it was easier,” she says. “The most I used to spend was $150 and that would get me whatever I need for the kids. That would last for maybe two weeks. Now, I don’t even get half of that and my bill comes up to like $200.”

Tabena visits the depot once a month. She says it definitely helps, but it’s not a resource she ever expected to be using.

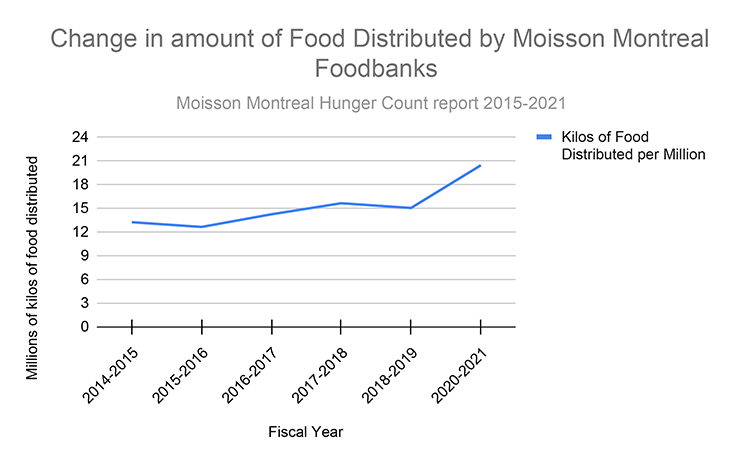

She’s certainly not alone. Visits to Montreal food banks rose 81.6 per cent between 2019 and 2021.

“It gets you into that depression where you feel helpless, and you just want to cry because I never really expected I would be looking for help from the food people. But I’m thankful that they’re there to help parents, mothers, kids.They helped a lot,” she says.

One of Tabena’s biggest challenges has been finding healthy food for her children and making sure they have lunches packed for school.

“There’s no help when it comes to that. You have to pack your kids lunch. If you don’t have anything you don’t want to send your kids to school. That is the problem. It looks like you’re not a fit mom. You’re not a fit parent,” says Tabena .

Customers pick up food baskets for 7% from a window on Duluth Ave in Le Plateau at Racine Croisée. Food Baskets are available from 4-6p.m on Fridays. Photo by Evan Lindsay.

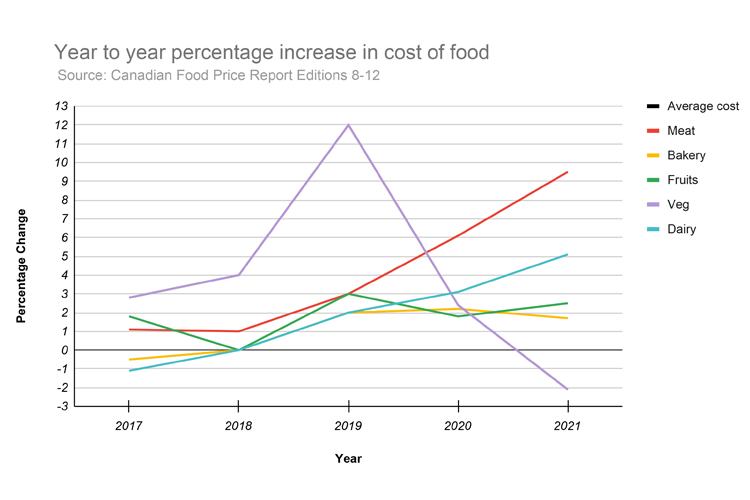

Even as jobs disappeared, food prices went up by 4.2 per cent in 2021. And the average price of groceries are expected to increase 5 to 7 per cent next year.

This graphic percentage change in the cost of different categories of groceries over the past five years according to the Canada Food Price Report. Media by Evan Lindsay.

According to Dr. Patrick Cortbaoui, managing director of the Margaret A.Gilliam Institute for Global Food Security of McGill University, the reason for continuing price increases is our reliance on trade for most food items.

“There is no local production, meaning the majority of our food that you see on your table or in your fridge is coming from outside the country,” says Cortaboui. “All kinds of ports, either by air, by sea or by land, were closed for several months, some of them still are. If you don’t have enough supply for the internal markets, you’re going to have shortages in those items required to survive. So definitely there will be price volatility because the demand is still high, but the supply is very short.”

A look into the supply chain issues and how grocery stores are dealing with increased demand. Video by Chantal Schromeda.

The rise of food prices and many people struggling to find work has led to a huge increase in demand at food banks.

“It’s been so hectic, like really hectic and really exhausting,” says Emily Balderston, the interim director of food security programs at the Share the Warmth food bank in Pointe-Saint-Charles.

According to a survey conducted by Moisson Montreal, the number of individuals who benefitted from food bank programs in Montreal increased 35.3 per cent from 2019 to 2021. Share the Warmth themselves gained 1470 new members during the pandemic.

The above graphic shows the increase in amount of food distributed by Moisson Montreal food banks over the past five years.

“We didn’t close once,” Balderston says. “There’s a part of that that’s really energizing and we’re really all happy to be a part of that. But also, we’ve had to adapt so much in the past almost two years. We’re always changing to respond to the measures and make sure everyone’s safe.”

Share the Warmth switched entirely to delivery during the pandemic. From July 2020 to June 2021 they delivered 10,460 food baskets. A massive increase compared to the 674 deliveries made before the pandemic.

An average food basket from Racine Croisée similar to those distributed by Share the Warmth. Media by Evan Lindsay.

They struggled to keep up despite receiving some emergency money from the government, private donors and an extra truck loaned to them by U-Haul.

“There was a while where we were really at our limit,” says Balderston. “Seeing that demand increase, trying to respond to it, having sometimes to say no, or having sometimes to say ‘you have to wait for your food for a week’ when people really need it. That’s really hard.”

Now Balderston says that some of the extra support is starting to go away. But they have gone from serving 470 households to 650.

“We’ve seen people hungry for years. There are more people that need it now. But there are a lot of people that need it regularly. A food bank isn’t just an emergency service for a lot of people, it’s a day to day reality,” she says.

Carrefour Solidaire has been fighting food insecurity for years. They opened a new grocery store called Trois Paniers in January of 2022, providing a unique resource to people facing food insecurity in Montreal’s Centre-Sud borough.

To Vanessa Girard-Tremblay, a co-executive director at Carrefour Solidaire, there is only one reason why people become food insecure and one real solution.

“It’s poverty. People don’t have the means to buy food or they don’t have means to buy quality food […] Basically, what we need to do is to raise income,” she says.

Vanessa Girard-Tremblay co-executive director at Carrefour Solidaire at Trois Paniers. Photo by Evan Lindsay.

Girard-Tremblay says that the pandemic has brought food insecurity to light in a way that’s made it easier for people who need help to ask for it.

“When Premier Legault said ‘go to your local food bank,’ it relieved people. People were like ‘okay maybe I should go, maybe it’s okay to go,’” says Girard-Tremblay. “People were ashamed to go to food banks, they still are.”

Trois Paniers is trying to create a new option for people experiencing food insecurity. At the store you can purchase healthy foods at three pricing options. The lowest price has no additional markup. The second has a small markup and the third price is the “pay it forward” price, which has additional markup to help to fund the store. The three pricing options give people more flexibility when buying their groceries.

Trois Panniers grocery store in center-sud, Montreal. Photo by Evan Lindsay.

“A bunch of people said that the prices were really low, which is good, because that’s what we’re trying to do. We’re trying to be as affordable as we can,” says Girard-Tremblay.

In addition to selling more affordable groceries. Trois-Paniers offers community meals twice a week and workshops for adults and kids in their kitchen in their effort to not only fight food insecurity; but, foster a sense of community.

“We’re trying to put together a system where people are dignified […] We’re really trying to create a grocery store where everybody can come and shop, and everybody can pay according to their needs,” says Girard-Tremblay.

Despite entering the late stages of the pandemic, many of the problems which have caused food insecurity, poverty and supply shortages, remain. According to the Canada Food Price Report wages and salaries for most people have not kept pace with the increase in prices.

For Dr. Cortaboui, unless we change our current systems of food production, the future won’t be much different.

“If we’re going to continue to copy and paste the current mode of production of food — if we don’t learn something from this pandemic — we’re going to see the same problems that we’re facing today.”