BY Zunayet Anis & Joshua Loon

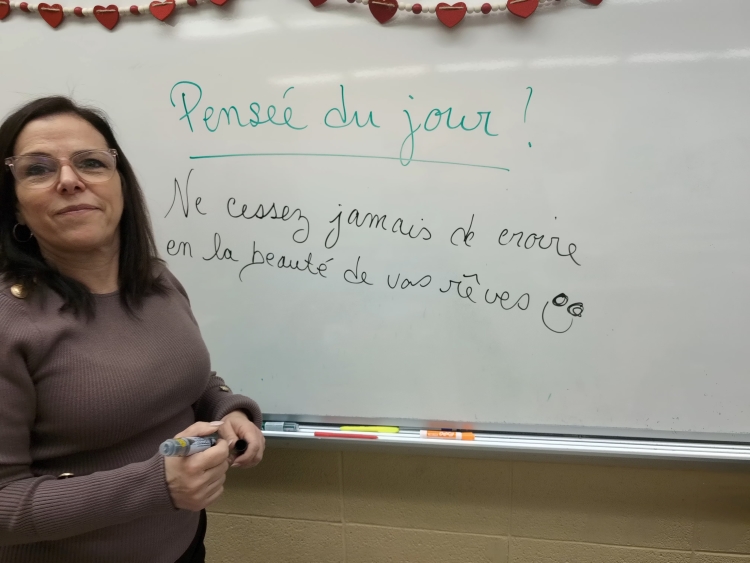

High school teacher Micheline Siag’s 35 years of experience helps her spot students who are losing interest.

“You can often predict who is going to struggle,” she says. “It starts small—missed classes here and there, slipping grades, a lack of participation. Then, before you know it, they’ve completely disappeared from school.”

“Students who are disengaged early on often don’t get the help they need until it’s too late,” Siag says, pointing out that early intervention is the only way of preventing dropouts.

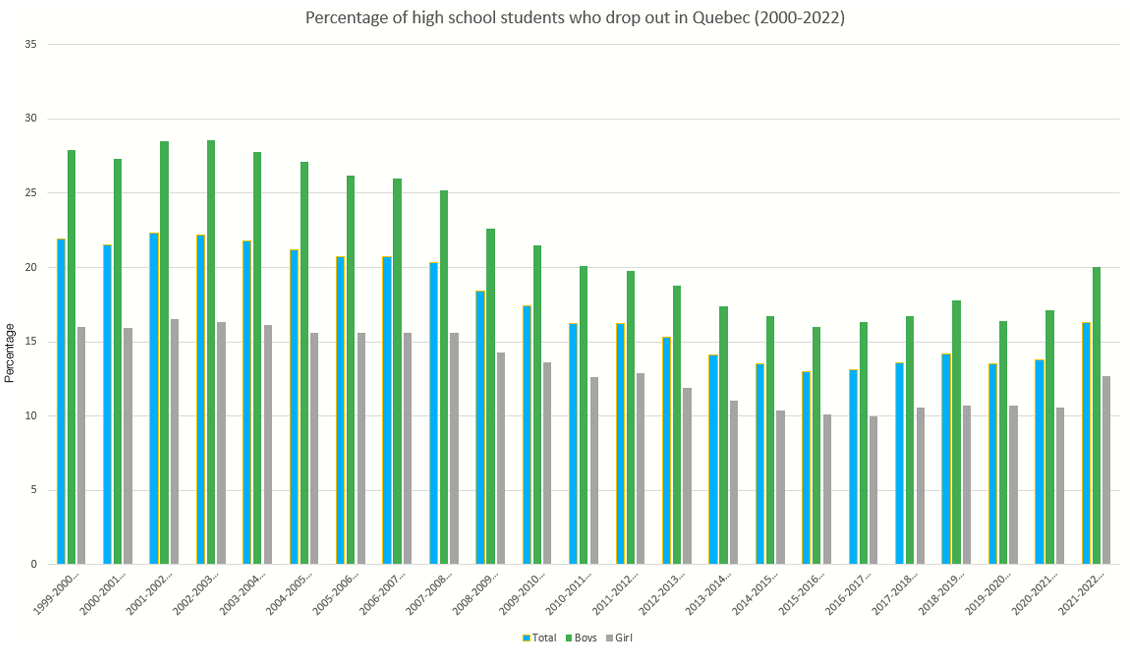

Quebec dropout rate evolution over 22 years. Infographic by Zunayet Anis.

For years, the conversation around high school dropouts has focused on boys being more likely to leave school before graduating.

Patrick Rakine is a veteran teacher. He says the way education is structured doesn’t always align with how boys learn.

“We expect them to sit still, take notes, write lengthy essays, and passively absorb information,” he says. “That’s not how many boys learn best.”

In many cases, boys struggle with the rigid structure of traditional education, which can feel constricting and unengaging. Instead of being offered opportunities to engage with the material in a hands-on, practical way, many boys are forced to conform to a model that does not cater to their learning style.

The list of grades of one of Siag classes. The passing grade is 60 per cent. Photo by Zunayet Anis.

Siag emphasizes that boys often thrive when they are taught more practically.

“Boys thrive when they’re given movement, structure, and practical, hands-on experiences,” she explains. “But in many schools, we don’t provide enough of those opportunities.”

There has been a rise in dropout rates among girls as well. Chrystelle Robitaille, an education expert specializing in dropout prevention, attributes this shift to the growing mental health challenges faced by young women.

“We’re seeing more students—especially girls—dealing with severe anxiety and depression,” Robitaille notes. “For them, school becomes an overwhelming burden. They feel immense pressure to succeed, and when they start falling behind, it can be paralyzing. Many simply give up.”

Adults returning to school after many years, dealing with personal struggles and the support resources available from the institutes in the Montreal area. Video by Joshua Loon.

Socioeconomic conditions also play a significant role in determining whether a student will graduate or drop out. Robitaille says students who come from families where education is not prioritized or where parents did not graduate from high school are more likely to drop out themselves.

“If their parents didn’t graduate, they may not see why it’s important,” she says. “If their family is struggling financially, getting a job can seem like the more practical choice.”

Another factor that contributes to the dropout crisis is the increasingly attractive option of entering the workforce at a young age. Quebec’s labor market has been experiencing a shortage of workers in various sectors, which means that many teenagers are able to secure employment—even without a high school diploma.

This creates a dangerous cycle where students, particularly those from low-income backgrounds, see the immediate financial rewards of working instead of staying in school.

“There’s a contradiction in government policies,” says Rakine. “On one hand, officials push for students to stay in school until they’re 16. On the other hand, they allow kids as young as 14 to start working. If you’re struggling in school and suddenly someone offers you a steady paycheck, school starts feeling like a secondary priority.”

This situation is particularly problematic for students who are already struggling academically and feel disconnected from the classroom.

To keep students motivated, Siag offers failing students to redo the assignment to reach the passing grade. Photo by Zunayet Anis.

Robitaille notes this is particularly true among young men who often gravitate toward jobs in construction or trades.

“For young men, especially, jobs in construction or trades can seem like an easy way out,” she explains. “Some of them are making $40 an hour by the time they’re sixteen.”

For young women, the story is different—many end up in retail or other low-wage positions that offer little in the way of long-term career growth.

Louis-Andre Bellemare has been working with at-risk dropout kids for the past 42 years. He emphasizes the long-term consequences of this mindset.

“Once they start making money, it becomes harder to convince them to return to school. They think, ‘Why should I sit in a classroom when I can make money now?’” he says. “But they don’t realize that, in the long run, their opportunities will be far more limited without a diploma.”

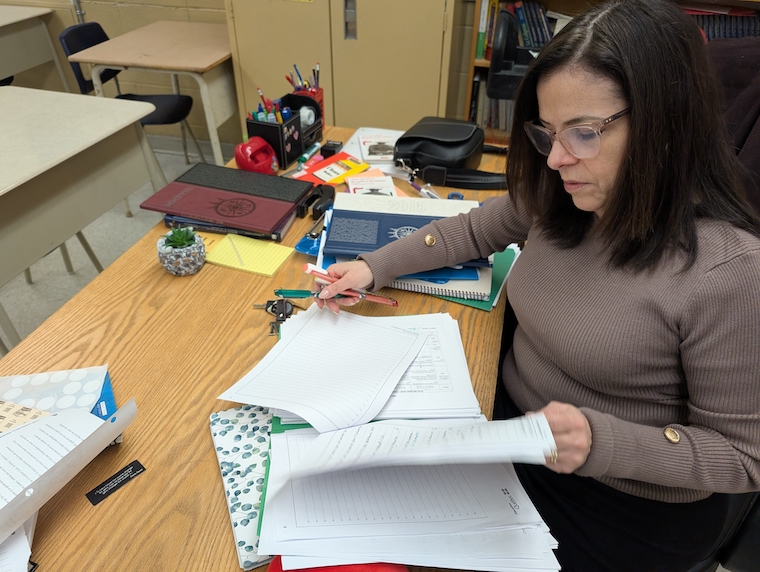

During grading , Siag notices the rise of use of artificial intelligence. Photo by Zunayet Anis.

One promising approach in the battle against dropouts is the expansion of mentorship programs. These programs provide students with the support and encouragement they need to succeed in school.

“If students feel like they have someone who believes in them and is invested in their success, they are more likely to stay engaged and motivated,” says Bellemare.

According to Bellemare, schools also need to incorporate more hands-on, vocational learning opportunities into the curriculum. This could include partnerships with local businesses, trade schools, or apprenticeship programs that offer students the chance to gain real-world experience while still pursuing their education.

Siag agrees, saying that the whole system needs to change.

“The way we present education needs to change. Right now, too many students see school as a place they’re forced to be until they’re allowed to leave.”