BY Charlotte Weissler & Sarah Maria Khoveiry

Rais Zaidi first took on food waste by diving headfirst into a dumpster, searching through piles of discarded but perfectly good food. Today he leads The Green Pirates, a nonprofit food bank backed by a crew of volunteers—or “pirates,” as they proudly call themselves—on a mission to rescue and redistribute food.

“There’s no such thing as ‘ugly’ or ‘not ugly’ food. You want carrots? These are the farm’s carrots; they’re all a bit crooked because that’s how they grow,” he says.

Rais Zaidi and his Green Pirates teammates getting everything ready before people come to pick up their food. Photo by Charlotte Weissler.

For Zaidi, there’s already enough waste, so they make use of everything they collect, regardless of imperfections.

They gather food from multiple sources—events, hospitals, bakeries—working not only to reduce waste but also to make food accessible to everyone.

“When people show up, I don’t care if they’re rich or poor, or if they need to prove how poor they are.That’s none of my business. I’ve got food: you want some?” Zaidi says.

He believes consumers need to rethink the way they buy their fruits and vegetables.

“We’re conditioned to expect perfection, to want the perfectly shaped pepper, the perfectly curved banana,” he says. “A tiny black spot doesn’t make a pepper any less good. But we, as consumers, are the first to reject it,” he adds.

Zaidi holds a tomato with a black spot. An imperfection like this can determine whether or not a vegetable makes it to supermarket shelves. Photo by Charlotte Weissler.

Despite growing awareness, perfectly edible food is still thrown away simply for not meeting cosmetic standards.

The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food of Quebec classifies produce into two categories: Grade No. 1 and Grade No. 2. Grade No. 1 must meet high aesthetic standards such as uniform shape, size, and colour. On the other hand, Grade No. 2, though still perfectly edible, may have imperfections like blemishes or odd shapes.

For example, according to the Quebec regulation on fresh fruits and vegetables, carrots smaller than ¾ inch in diameter are classified as Grade No. 2.

Gabrielle Dessureault, project coordinator for Sauve ta Bouffe, an educational initiative tackling food waste, says this system of standards makes people see imperfect produce as inferior.

“Of all the foods I grow in my garden, it’s very very rare that there’ll be much of them between seven and nine inches,” she says.

‘Ugly’ products are sometimes discounted to encourage sales. While this can help reduce their waste, it also reinforces the idea that they’re less good, of lower quality, she adds.

“The ones that are less pretty are less expensive, but they’ve used the same resources as the ‘pretty’ ones,” Dessureault says.

She mentions the TooGoodToGo platform as an example of a solution working to tackle food waste. It allows consumers to purchase surplus food at discounted prices from local businesses, helping to reduce waste while also making food more accessible. According to Dessureault, initiatives like this are part of the growing movement to change how we view food, showing that imperfect products still have value and can be put to good use.

Sauve ta Bouffe offers a practical guide of tips and tricks to apply on a daily basis to avoid food waste. However, how we view food is deeply ingrained in our shopping habits.

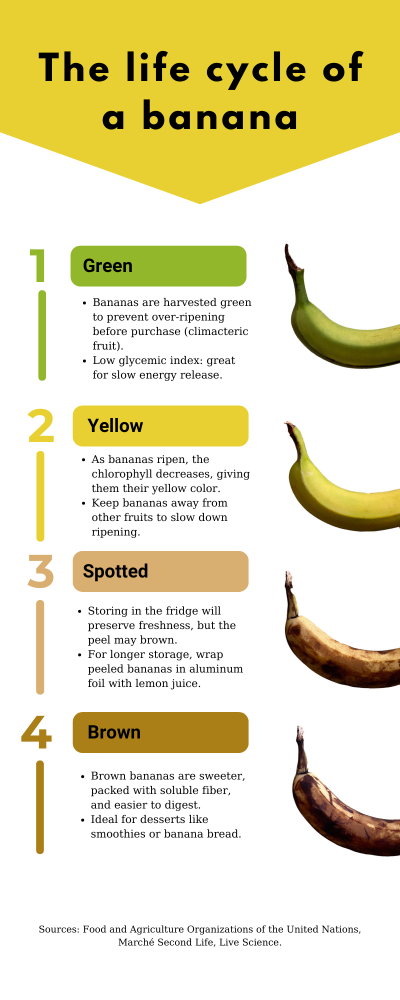

One example is bananas, a fruit commonly received by food banks like the Green Pirates and one of the most widely produced, traded, and consumed worldwide—yet often wasted.

Sauve ta Bouffe highlights a simple way to reduce that waste: banana peels don’t have to be thrown away. If organic, they’re entirely edible and packed with nutrients. Just wash them well, then cook, boil, fry, or blend them into recipes.

A case study: the life cycle of a Banana. From green to brown, discover how to make the most of bananas. Infographic by Charlotte Weissler.

According to Pascal Thériault, vice president of the Order of Agronomists of Quebec, we always start our shopping in the fruits and vegetables section because it is the most colourful, naturally drawing us into the shopping mood. However, while cosmetic standards make food visually appealing to consumers, Thériault points out that they also contribute to food waste.

“When you buy a lettuce, you pay for all the others that were discarded,” he says.

The cost of saving imperfect produce often exceeds the revenue that could be generated from selling it, Theriault explains. Large producers might donate good but slightly damaged products to food banks, but only if there’s enough surplus to make it worthwhile. On farms, ‘ugly’ produce is usually turned into fertilizer instead of being thrown away.

“No producer wants to waste,” he says.

The 2024 report from Second Harvest shows that over 46 per cent of all food in Canada is wasted each year. Avoidable food waste—food that could be repurposed or donated—has risen by 6.5 per cent, contributing approximately 25.7 million metric tonnes of CO₂ emissions annually.

Erik Chevrier, a food activist and scholar, works with CultivAction, a cooperative of urban farmers in Montreal. CultivAction works to reduce waste by donating blemished items to volunteers, selling them at a discount, or repurposing them. They also make sure that anything that can’t be saved is composted and returned to the soil.

“A lot of people judge food by the way it looks rather than the way it tastes—and little blemishes convince people that the food is not edible,” Chevrier says.

Fruits grown outdoors are subject to varying weather conditions, and organic cultivation usually leads to small blemishes, he explains. But imperfections don’t mean bad food; they’re a natural result of growth. In fact, he notes that farm-grown fruits have more flavour due to their natural environment.

Local and sustainable agricultural initiatives provide restaurants with produce to serve authentic sub-Saharan food. Video by Sarah-Maria Khoueiry.

Chevrier says the key to reducing food waste lies in reconnecting people with their food. He explains that there are many ways to use imperfect products, especially when we are cooking them.

“People wouldn’t even notice [that imperfect produce was used]. For a tomato sauce, you just cut off the part of the tomato with the bug bite, and well, you’re okay!” he says.

Yet, imperfect produce remains hard to find in grocery stores. Instead, consumers must turn to farmers’ markets or online platforms, bypassing traditional retail norms.

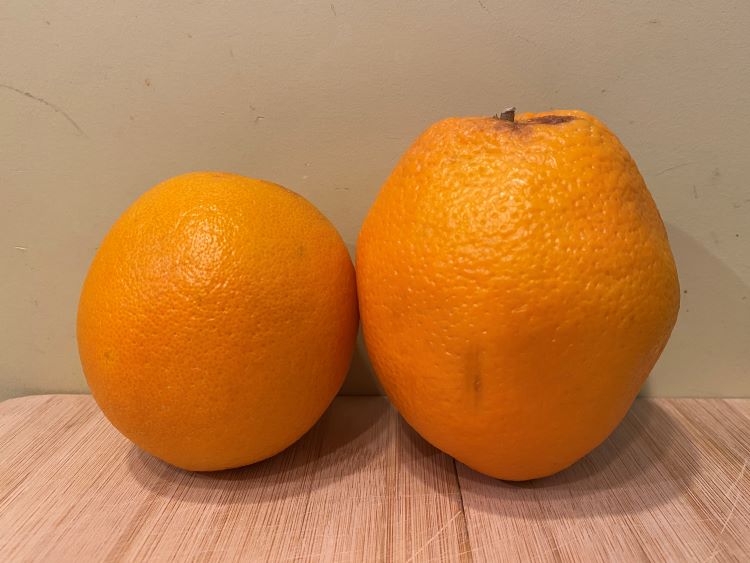

Marché Second Life is one of them, working to rescue No. 2 products that would otherwise be discarded due to strict norms. Anthony Berne, the buyer and delivery supervisor, explains that they recover surplus food from farmers with excess crops or from retailers who reject items for being too curved, oversized, or blemished.

Two oranges: on the left, a standard supermarket variety; on the right, an oversized, misshapen one from Second Life, that would have been wasted for not meeting aesthetic standards if not rescued. Photo by Charlotte Weissler.

“People have to get past the appearance of a crooked, small, or damaged product; it just doesn’t fit the standards that you’re seeing on television,” he says.

However, sorting these products is a challenge. Berne notes that about 50 per cent of what they recover is too deteriorated to save due to mold or spoilage. To make use of what they can, Marché Second Life offers affordable, customizable food baskets filled with No. 2 produce, helping consumers reconnect with the reality of how fruits and vegetables are actually grown.

With high food prices, Dessureault says consumers are reluctant to buy imperfect products, fearing they won’t get their money’s worth.

“Knowing grocery prices right now, we want food to last, but imperfect, slightly crooked vegetables will last just as long,” Dessureault says.

As Quebec grapples with these challenges, Dessureault points to France’s 2020 Anti-Waste for a Circular Economy Law, passed in 2020lawsuppliers to donate unsold food to charities rather than throwing it away.

Zaidi agrees that stronger regulations are needed.

“It’s always surprising to see people still wasting food in 2025. It feels like everyone is aware of issues like food insecurity and waste in general—it just doesn’t make sense,” he says.

For him, being a better consumer starts with buying local and directly to the farmers, supporting food systems that prioritize sustainability over aesthetics.

“At the farmers market, there are all the vegetables from the farm, not just the pretty ones,” he says.

Carrots received in a basket from Second Life, rejected by cosmetic standards for their small size and odd shapes. Photo by Charlotte Weissler.

While it’s more complicated in cities, he points out that Montreal has plenty of markets where people can support local farmers.

All across Quebec, numerous initiatives are working to challenge the strict norms surrounding imperfect produce, highlighting the need to rethink how we value and buy food.

The Green Pirates are currently operating from a temporary space and are unsure of their next location, but they said it’s only the beginning of this adventure.

“I have big plans, it needs to get even bigger,” Zaidi says.